Timothy B. Conley, Ph.D., LCSW, CAS

Associate Clinical Professor of Social Work

Yeshiva University Wurzweiler School of Social Work

Michael Serrano, Ph.D., LCSW, CASAC

Adjunct Professor at Wurzweiler School of Social Work

The Epidemic

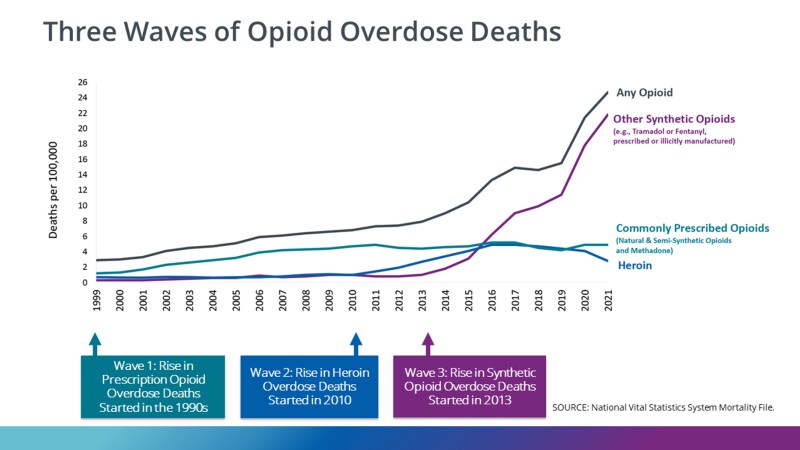

When beginning to discuss the opioid epidemic and related treatment workforce development issues, a picture is worth a thousand words. This chart is from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

There is no good news here. We can use the visual as a proxy for the degree to which not just fatalities but opioid-related substance use disorders (SUDs) in general, have climbed steeply in the new millennium. For every fatality, there are dozens of thousands more individuals who have become severely addicted to opiates, are living desperate lives, and are seeking assistance to change. They have family members who need help and guidance, as well. Many will recover their lives; opioid dependence is not always a death sentence. But for those risking their lives using opioids, the question most often asked is why? Why, in the face of devastating and fatal consequences, would an individual choose to continue to obtain and use potentially lethal substances?

Choice? What Really Constitutes Opioid Use Disorder

There are many theories of addiction, but all agree: The afflicted individual, at some point, loses control over their own substance-seeking and substance-taking behavior. Think of it: They cannot control their behavior no matter how hard they try, despite devastating damage to their life. In essence, they are continuing to use substances despite sincere and powerful (but compromised) intentions not to do so. It becomes a compulsion over which the individual, at the time, has no control. This is true for several classes of substances, not just opioids. Consider tobacco and nicotine products, for example. Over 480,000 people in the U.S. die each year due to the compulsive use of this substance, and an overwhelming majority had a longstanding persistent desire to quit.1 Most tried repeatedly but never regained control. Once again, let’s ask why?

The most widely held theory of addiction is codified in the 11 criteria, or symptoms, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Revised (DSM-5-TR) by the American Psychiatric Association. These criteria mirror those used by the World Health Organization. To answer our questions about why people use substances (i.e., opioids, tobacco) to the point of fatality, we will consider two criteria here: tolerance and withdrawal.

Tolerance

The principle of tolerance states that once an individual takes one of these substances, very soon, they will get less effect from taking that initial amount. In essence, they get less effect from the same dose, so to get the effect (in the case of opioid pain relief), they will need to take a larger amount. This is progressive—achieving the same effect just keeps requiring more of the substance.

Withdrawal

Withdrawal comes when an individual has been taking the opioid regularly and then stops. Symptoms of withdrawal are legendary and include sweating, shaking, itchy goosebumps, diarrhea, vomiting, headache and a host of other uncomfortable experiences. The smaller the dose and the shorter the time using the substance, the less uncomfortable withdrawal will be. But if tolerance is very high, the withdrawal is literally torture. The addiction is established when the individual takes the substance to avoid the withdrawal that comes from not taking the substance. Smokers most often think they are having a cigarette to relax, but in truth, they are taking a dose of nicotine because without it, the sickness and the withdrawal advance. It is the same for opioids but with an even more severe withdrawal syndrome and much more immediately fatal consequences.

Addiction is an Illness That Requires Multi-Faceted Treatment

There is an overwhelming need to recruit and retain addiction treatment professionals who are capable of providing the type of services needed to meet victims of the epidemic. Academic training institutions are not equipped to keep pace with the rapidly growing need for service providers. In essence, the infrastructure for generating new qualified and motivated providers is not in place.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment of substance abuse, behavioral disorder and mental health counselors is projected to grow the fastest among the mental health occupations, increasing 18% from 2022 to 2032.2 Through 2036, the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) projects a shortage of 87,630 addiction counselors and 69,610 mental health counselors due to the growing demand for behavioral health services and the insidious impact of the opioid epidemic.3 This is, at best, a conservative estimate, for while some effective and practical steps to address the opioid epidemic are being taken, there is a rise in the use of other substances with highly addictive potential, such as ketamine and concentrated cannabinoids.

Addictive disorders, whether for opioids or tobacco products, need medical intervention and treatment but that is just the tip of the iceberg. Underlying every addiction is a family, employer and community, all of which need facilitated healing not done by the medical profession. An ideal education to be a leader (program manager, clinical director, policy writer, etc.) in the addiction treatment workforce is an MSW degree with a credentialed specialization in addictions.

What Wurzweiler School of Social Work is Doing in This Area

Wurzweiler began overhauling its lone addiction course in 2017 and by 2020 had three full electives. This became the Joint MSW/CASAC Training Program and the school was approved by the Office of Addiction Supports and Services Workforce Development and Talent Management Bureau, Learning and Development Unit, as an Education and Training Provider for addiction education in New York state (ETP#1381).

Preparing a social work workforce trained in treating both SUDs and other mental illnesses is vital. At Yeshiva University, we now offer a comprehensive, 60-credit online Master of Social Work (MSW) program with an addiction concentration, which thoroughly prepares future social workers by empowering them to develop the needed skills, knowledge and aptitude to work with the population. Encompassing three elective sequence courses: Social Work Practice with Addictions I, II, and III, the graduate student curriculum covers the history of the addiction profession relative to social work, models and theories of addiction, neurobiology of addiction, effects of substances, assessment, screening, and treatment, evidence-based practice, crisis intervention, relapse prevention, harm reduction, opioid overdose prevention, ethics and cultural diversity. Not all SUDs are the same, and the course content specifically addresses opioids with modules on Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) and intense case studies. Practitioners are uniquely positioned to graduate with an MSW and a New York State educational certificate to apply as a Credentialed Alcohol and Substance Abuse Counselor (CASAC). If you are passionate about this as much as we are, join us today to fight against the growing problem that individuals and communities continue to face.

To get started, schedule an appointment with one of our admissions outreach advisors.

- Retrieved on May 29, 2024, from cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm

- Retrieved on May 29, 2024, from bls.gov/ooh/community-and-social-service/substance-abuse-behavioral-disorder-and-mental-health-counselors.htm

- Retrieved on May 29, 2024, from hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/Behavioral-Health-Workforce-Brief-2023.pdf